It was the summer between fourth and fifth grade, in Phoenix, Arizona. By the time fourth grade ended, I was on my tenth school, including kindergarten. Four in the fourth grade alone. Fifth grade would be the first time I started a new school year in the same school where the prior year ended.

I liked baseball. I wanted to play in Little League. And it was tryout day on the ball field. Kids were in uniform everywhere, talking to dads, practicing, playing catch. Coaches and dads huddled near the first and third-base benches, pointing and evaluating. Dads hit grounders to their sons, who fielded and threw to an imaginary first base. Others hit fly balls to eager sons in the outfield, who circled underneath and made their catches.

Everyone knew everyone.

Except me.

I was by myself. In my cut-offs and an undershirt. And tennis shoes. I’d never fielded a ground ball in my life. And nobody seemed interested in teaching me.

The tryout was simple. Field a ground ball and throw to first. How hard could it be?

I watched boy after boy charge ground balls, scoop them up and fire to first. I practiced the motion in my mind, watching and learning and evaluating.

It was my turn. A coach hit a slow roller. I decided it didn’t make sense to charge it—too many chances for error. The ball rolled into my glove, I stood and threw to first. It was a decent throw. That was it. Tryout over.

Other kids tried different positions. Some took a few at-bats. Some ran the bases. A few practiced sliding. But nobody invited me. One ground ball. Sometimes, opportunity only knocks once.

I watched for a while, and then hopped on my bicycle and pedaled home. Alone.

#####

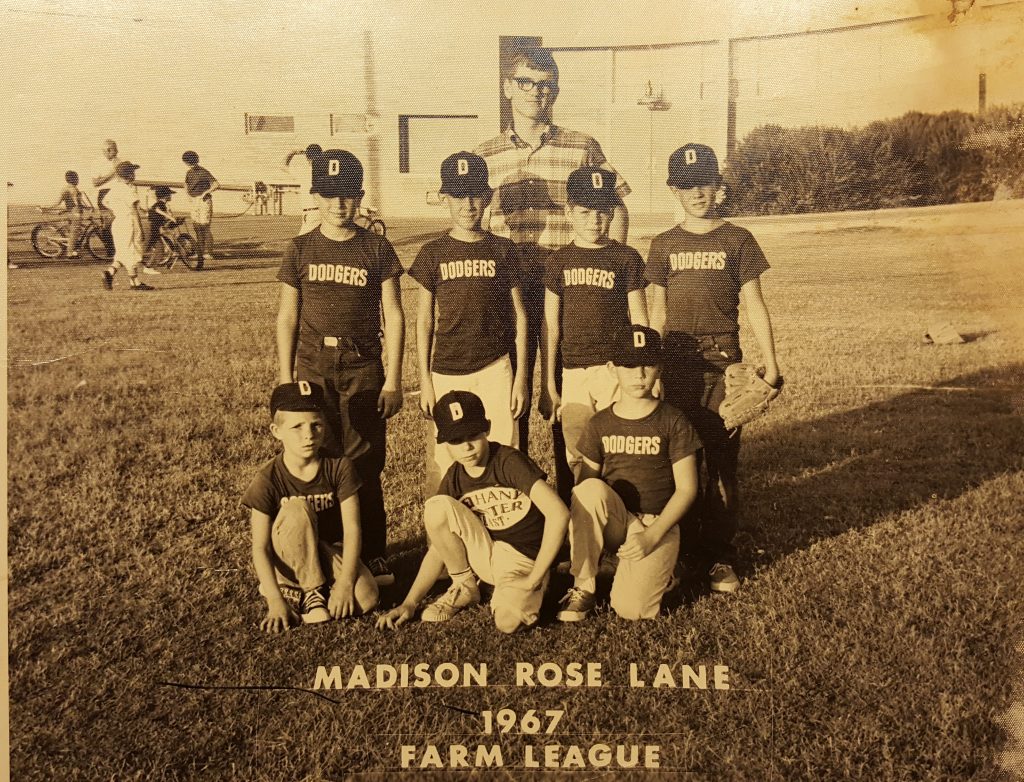

The phone rang a few days later. I was on the Dodgers. No, not the major league team where kids wore white uniforms with striped pants, but the farm team, where kids wore colored tee-shirts with an ad on the back.

Our team only had nine players. Some games, only seven players showed up and we had to borrow from the other team. We rarely practiced and we never won a game.

But I practiced, because I wanted to pitch. During the warmup before our first game, I wanted to try my fastball, and so I asked another player to catch for me. My first pitch left my hand too early and flew over a backstop and into a parking lot. Nobody wanted to catch for me after that.

Sometimes, I threw at a homemade target on the fence and imagined myself on the pitcher’s mound in a real game. And after a while, I was pretty good at hitting that target.

Game after game, I asked if it was my turn to pitch. Game after game, Coach Dennis gave the same answer. “Not yet, maybe later.” I never did understand how Coach Dennis picked pitchers, only that everyone was supposed to have a chance to play every position. But he put me in the outfield almost every game.

My turn to pitch finally came at the end of the season.

“Ready to pitch an inning?”

My heart jumped. “Yeah.”

“Okay. Just take it easy. Don’t try to throw too hard.”

I trotted to the mound and took my warmup pitches. Just some easy tosses to the catcher. Coach Dennis said don’t throw too hard.

“Batter up!”

I wound up.

My teammates went into their chant. “Hey batter batter batter, hey batter batter batter.”

The ball bounced in front of the plate.

“Ball.” Barely audible. The ump yawned. He took off his facemask and cleaned his glasses. Parents in the bleachers behind the plate talked to each other. The opposing coaches chuckled. My infielders made little designs in the dirt with their feet and looked down. The outfielders shifted on their legs.

The catcher tossed the ball back. The throw was off. I had to jump to catch it. I glanced at Coach Dennis. He looked ready to fall asleep.

I surveyed the scene around me. I remembered my non-tryout. I remembered all the chances given to everyone else, but not me. And I made a decision.

This is crap. I’m gonna throw hard.

I wound up again.

“Hey batter batter batter, hey batter batter batter.” It sounded like a record player turning just a little too slowly.

And I let one fly. Pop! It sounded like a rifle blast.

The catcher pulled his hand out of his mitt and shook it. The batter’s jaw dropped. Parents’ heads turned. The opposing coach looked up. Time stopped.

The umpire’s eyeballs looked ready to pop out of his head. He looked at the catcher. And then me. And then at the catcher again. And then shook his head and jabbed his right index finger in the air. “Steeee-rike one!”

Am I in trouble for throwing hard?

Coach Dennis was smiling. Maybe not.

The catcher tossed the ball back. The throw was chest-high. And crisp. The umpire dug in. So did everyone else.

Three batters walked back to their bench, shaking their heads, that inning. I walked off the mound, smiling. I wasn’t worthless.

“Hey coach, can I pitch another one?”

“Maybe later.”

#####

More than forty years later, I attended a conference in Boston for my job. The conference organizers rented Fenway park that evening and treated us to the best ballpark food anywhere. As I was leaving, I noticed a booth with a backstop and radar gun. The sign said, “try your hand.” I waited and watched lots of younger guys impress their wives and girlfriends. And then it was just me. And the booth. And a few baseballs. And a radar gun.

I wound up and let one fly. The radar said 55 mph. Not bad. But I figured I had more. The next one was 57 or 58. I tried a couple more and hit 59. By now I was loose. I wound up and gave it everything I had. The throw was wild. Had there been a batter, somebody would have gotten hurt. The radar gun registered 60. I smiled.

#####

That night at Fenway Park, I proved I don’t have any special pitching talent. But when I look back to that day in the summer of 1967 in Phoenix, Arizona, I wonder if God sent a crew of angels to help out a scrawny kid with self-esteem problems? Because, for that one day, I had supernatural pitching talent. And it felt good.

I’m not worthless.

Recent Comments