When Doug Bean brought me a pretzel snack pack, I was suspicious of that first pretzel stick. Grownups always wanted me to try some new food and I almost always regretted it. But Doug promised—just try one, and if I didn’t like it, I wouldn’t have to eat any more. And so, I gave in. Wow, that was good. So was the next one. And the one after that. And before long, I’d eaten the whole box. As a six-year-old, I didn’t know much about snacks, but I knew right then and there, I liked pretzels. More than fifty years later, I still like pretzels.

I call my biological dad Doug because after my mom remarried, I called my stepdad dad, and so the word, dad, still sounds weird with Doug.

Doug and my mom divorced when I was two years old. Mom said he drank all their money and gambled away what he could borrow, leaving her to spend years paying off his debts. Other than that, she didn’t talk about Doug much, but even a six-year-old boy could figure out she didn’t like him. And since mom didn’t like him, her son had his suspicions.

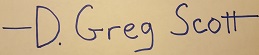

But Doug always treated me well. Sometimes he took me to the Twin Falls, Idaho, Elks Club. Bowling balls rumbled down the lanes and clattered against their pins every few seconds while we made our way to the coffee shop. The coffee shop was bright and cheery, and the waitresses wore yellow uniforms. I always ordered a hamburger, french fries, and potato chips. And 7-Up. The waitresses cooed over me and asked how I could eat so much and stay so skinny. Looking at Doug, it ran in the family.

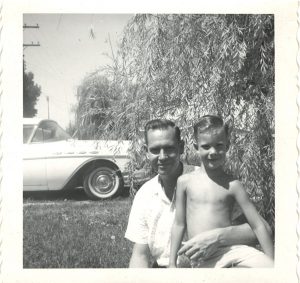

In early 1966, I was eight years old and Mom and I lived in Tucson, AZ. It had rained, and the dirt had turned into mud and then partially dried. The ground looked like grey lizard skin under a magnifying glass. Doug was in town and wanted to take me to dinner and spend the night with him in his hotel room. He wore dress shoes and I tried to direct him away from the not-yet-dried mud squares. He stepped right in the middle of one, but acted like he didn’t care if his shoes got dirty.

Mom was sure he had friends in high places and was afraid he’d try to kidnap me. But I talked to mom and promised I would escape if he tried anything. Mom finally agreed to let him take me for the night.

After dinner and back in Doug’s hotel room, I decided I would only pretend to sleep when he turned off the light. All I needed was a little time for my eyes to get used to the dark. And then, if he tried anything, I would squirm away and run and yell as loud as I could. And I could yell louder than anyone I knew.

I wanted to lie on the bed with my clothes on, but Doug insisted we sleep under the covers in our underwear. That put a kink in my plan, but I could still make it work. Maybe I could grab my pants as I ran out of the room, screaming. But realistically, the pants might have to be a casualty. Grownups would understand. I had more pants at home. It was a good plan. I was prepared. Just in case.

“Time to wake up, son.” It was morning. We ate breakfast and Doug brought me home, as promised.

Summer, 1966, mom and I were at the Holiday Inn in Albuquerque, New Mexico, one step ahead of the bill collectors. Daniel Gregory Bean and Francis Bean ceased to exist that summer, and Daniel Gregory Scott and Staci Scott appeared out of nowhere.

I woke up one morning and mom was on the phone. Somehow, Doug had tracked us down and called her. She told him we were headed to Florida. But we never went to Florida. We ended up in Phoenix.

I wouldn’t talk to him again for fourteen years. But I remembered the pretzels, I remembered the Elks Club hamburgers, I remembered the overnight visit in Tucson, and I remembered the phone call in Albuquerque. And I was curious. But not curious enough to do anything about it.

Until 1980, when I told my new wife, Tina about all of it. Tina encouraged me to contact him. What was I afraid of, she asked. I couldn’t come up with an answer.

For any fathers reading this, you need to know that your young children will remember how you treat them well into adulthood. I reached out to Doug as an adult, partially because Tina hounded me, but mostly because I remembered he tried to stay connected to me when I was a boy. I’m glad I did.

I found two people in Idaho named Doug Bean and figured the one in Boise was most likely him. I dialed the phone and told him who I was. His voice quivered as he said, “Why—you’re my son.” I told him how we never went to Florida and how I was alive and well and living in Indiana with my new wife. And I apologized that we lost touch. I’m grateful to Tina for persuading me to call him. Husbands, listen to your wives.

When we see reunion scenes in movies, it’s always emotional and the characters usually cry. Because now they’re both complete after finding their missing pieces. It wasn’t that way with Doug and me. The quivering in Doug’s voice told me it was a big deal to hear from his adult son after fourteen years, and I know it was a big deal for me to connect with him. But I wasn’t sure what to feel.

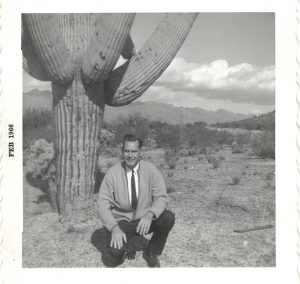

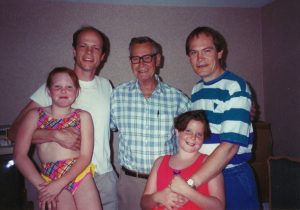

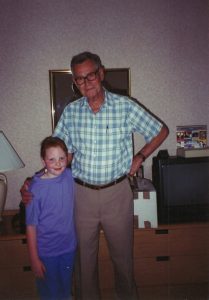

We visited a few times over the years and we fully reconciled. I still remember him rolling around on the floor with my ten-month-old daughter in 1987. We talked about Christianity in the 90s. I don’t know when he accepted Jesus. Probably before I did.

Doug and I have some things in common. We both have long, bony fingers. He played professional baseball with the St. Louis Cardinals’ organization after WWII. I enjoy softball. Year after year, he pitched skit ideas and whole scripts to the Bob Hope Show and others of his era. Everyone either ignored him or turned him down. I published two novels so far, and pitched more media outlets than I can remember.

He was about as Type A as it gets. He was set in his ways and stubborn as a mule. He remembered my healthy appetite as a boy, and so every time we visited, he took us to an all-you-can-eat buffet restaurant, where I stuffed myself. He never let me pay.

And he didn’t like touchtone phones. Too high tech. I do high tech for a living. Doug and I were not clones.

I asked him about his marriage to mom. He said it was a bad marriage and mostly his fault. And that’s all he would say about it.

In November, 2002, he was in the hospital. Everyone knew he was not coming home, and so my teenage daughter and I flew to Boise to say goodbye. We found him hooked to IV tubes and wires in a room filled with beeping monitors. He had trouble staying alert. Cigarettes had taken a toll and he couldn’t talk because of a breathing tube in his throat.

After he saw my daughter and me, he badgered his nurses with hand signals to remove that breathing tube until they finally said yes. The best he could manage after that was a hoarse whisper–but that was good enough to ask his nurses out on dates. I have a hunch some of them wanted to put the tube back in.

When it was time to catch our flight home, I stayed at the hospital a few extra minutes and then rushed to the airport. That was the day Boise Airport decided to enhance its security, and by the time we made it to the gate, ten minutes before scheduled departure, the plane was sitting at the end of the jetway and the jetway door was closed. Did I mention it was ten minutes before scheduled departure?

Doug would have been proud of me that day because I refused to accept defeat without a fight. I stood in front of the window and jumped up and down and waved my arms at the pilot in the cockpit in the plane at the end of that jetway. When he turned his head toward me, I made a giant “come here” motion. Maybe a dozen times. Maybe more. My daughter looked like she wanted to crawl under a chair and hide.

A few seconds later, a lady came through the jetway door and asked what I wanted. I told her I wanted on that airplane. She got on her radio and said, “there’s been a break in security. Push back.”

I protested. She didn’t care. I protested even more while the plane pushed back from the gate and taxied away. My daughter wanted to become invisible, but I felt it was my duty to point out to the gate agent, and anyone else within earshot, that she made a mistake by sending the plane away without letting us on. And I may have also offered a few helpful suggestions about how to run an airport better. We finally booked the first flight out the next morning and I called my half-brother, Steve, to come get us. One more night in Boise.

We slinked back into Doug’s hospital room and when he saw me, he sat up and said, clear as a bell, “Get me on my feet!” He tried to disconnect the wires and tubes from his body and swing his legs over the side of the bed. He was going to drag me out that hospital, stuff me in his car, and get me to the airport and on that plane, one way or another, no matter what. It took all of us to keep him in bed while we explained over and over, the plane already left and I was staying one more night.

I couldn’t help but laugh. He finally settled down, but not without a fight. That’s the way I want to remember Doug Bean. Fighting ‘till the end.

We left the next day. My daughter and I were at the airport around 4 a.m. and I saw the same lady responsible for my extra night in Idaho. We made eye contact and I said, “How ya doin’? I’m back!”

She put a wand in front of my chest and said, “Sir, you’ve been selected at random for a more thorough search. Please step over here.”

“Random, huh?” I laughed. My daughter wanted to hide.

Doug died a few days later. He probably gave Jesus a piece of his mind when he first saw Heaven.

(I want to thank my daughter for correcting my memory around Doug’s breathing tube details.)

Recent Comments