As my mom, my fiancé, Tina, and I approached the Mai Tai restaurant in Excelsior, Minnesota, Mom said, “Let me do the talking.” It was spring, 1978 and Mom’s 51st birthday was a couple months away. She looked like an aging Hollywood diva.

A maître d behind a podium inside asked, “May I help you?”

“We have reservations,” Mom said.

“Name, please?”

“Staci Gent.”

The maître d checked his list. Mom knew we weren’t on it. She also knew people needed reservations to eat here.

“I’m sorry, I don’t see your name on the list. Perhaps it was for a different day?”

“No, it was for right now. I made the reservation myself.”

“I’m sorry, but we don’t have a reservation for you.”

“You should be sorry. It’s not my fault you screwed up.”

Tina and I shifted on our feet. I looked away. The maître d seated us.

#####

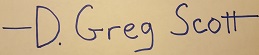

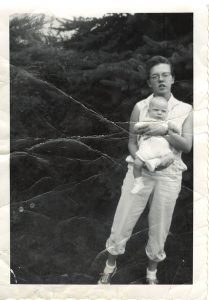

I want to remember Mom as a survivor who could outwit and out hustle anyone and win. Not because she was stronger—at barely taller than five feet and 100 pounds, she wasn’t—but because she was smarter.

My sister is twelve years older than me, which means Mom must have been eighteen years old when she gave birth to my sister in 1945. Imagine an eighteen-year-old single mom, raising a daughter alone in the late 1940s and 1950s America. She had no equal opportunity laws, no public assistance, nobody to turn to for help, and, no doubt, plenty of scorn from just about everybody.

She gave birth to me in 1957, an accident from an unhappy marriage. She divorced Doug Bean two years later, now with a toddler and a teenager to feed. Somehow, she raised my sister and me. But by 1978, alcohol and cigarettes and the world had taken a toll and her diva act didn’t work. Except with upscale stores and restaurants where everyone was happy to play along and let her spend money.

Tina and I talked about that incident at the Mai Tai later. We decided the maître d probably knew exactly what Mom was up to, but it wasn’t worth a fight to call her bluff. After all, she did intend to spend money. It was midafternoon, between lunch and dinner, so there were plenty of tables. As I look back on that day, I’m not sure who played whom.

#####

Mom liked to call herself a bohemian.

It was late April, 1966 and I was eight years old and about to finish third grade. Mom, my sister, and I were at a shopping mall in Tucson, Arizona, and Mom noticed a couple of artists drawing chalk portraits. We got in line for our portraits, and next thing I knew, Robert Scott and John Gittens were eating dinner at our dinner table. They stayed overnight, they stayed the next day, and they stayed the next several days after that. Robert Scott slept with Mom. I don’t remember where John Gittens slept.

“Greg, wake up.” Mom, hovered over me.

“Huh? Why? It’s Saturday.”

“Get up. We’re going to Canada.”

“How long will we be gone?”

“I don’t know.”

“What about school?”

“School’s almost done anyway. Hurry up. We’re leaving.”

I never finished third grade.

In a hotel room on the way to Winnipeg, I drew my plan for the ultimate military airplane, including specifications for super thick steel. I’d watched Twelve O’Clock High and saw plenty of planes shot down on TV. I don’t remember how thick I made the steel in my drawing, but I made it thick enough that no bullet would ever shoot down my plane. Robert Scott shot it down.

“This is art, not a number! You don’t put a number in art, what’s wrong with you?” He wouldn’t shut up about it. And the more I tried to explain this was a plan and not an art drawing, the madder he got.

Mom said artists think differently than most people and it wasn’t a big deal. John Gittens apologized in his British way. I decided not to show Robert Scott any more drawings. Or anything else.

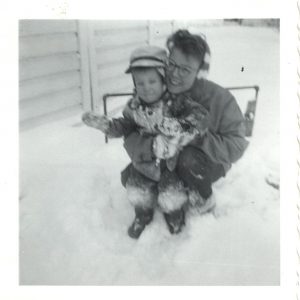

We made it to Winnipeg and stayed in a hotel while Robert Scott and John Gittens drew chalk portraits in a local shopping mall. I ate lots of chicken and the sun stayed up past 10 p.m. When people asked me about my dad, the artist, I wasn’t sure how to respond. But since we were using his last name, I played along with whatever they said. Somewhere in our Canada tour, we celebrated Canadian Independence Day on July 1.

In Brandon, Manitoba, Mom packed our stuff into our white 1963 Chevrolet Impala and we left. Mom said Robert Scott was a dreamer and life with him would be nothing but pain. We left Canada behind, but kept his last name. Daniel Gregory Bean and Francis Pepper Bean disappeared. Daniel Gregory Scott and Staci Pepper Scott appeared out of nowhere.

Years later, I asked Mom about that summer. She told me Robert Scott was experimenting with drugs and that was why we left. Why choose Staci for a first name? Because she liked the way it sounded. We made my name official in 1978 so I could get married. It’s all documented on a piece of paper in a vault in the basement of the Hennepin County Government Center in downtown Minneapolis.

Mom and I headed south and stopped at a camp site in the mountains near Taos, New Mexico. Mom and I weren’t homeless, we were bohemians, sometimes staying at the Albuquerque Holiday Inn, sometimes at that camp site near Taos. I never found out how Mom paid for that hotel room. My only clue is, she said the Assistant Manager liked her.

Mom warned me that New Mexico Indians had a reputation for being drunk and mean. And one morning, I woke up from the back seat of our car and found her standing next to the dirt trail leading to our campsite, talking to one.

I wandered over to say hi and Mom turned to me and said, “Greg, go find your father and tell him it’s time for breakfast.”

“Huh?”

“He’s back in the woods, fishing. Go find him and tell him it’s time for breakfast.”

“What?”

“You heard me. Go find your father. Don’t make me ask you again.”

She gave me a look and the lightbulb in my head turned on.

“Oh. Um, yeah. Okay. I’ll go get him.”

I strode past the car and picnic table toward the stream, and then paralleled the stream into the trees and out of sight. I wasn’t sure how I would pull this off, but Mom was counting on me. Where was a park ranger when you needed one?

“Hey Dad, where are you? It’s time for breakfast.” Now, what?

I ran farther into the trees and answered with the deepest voice I could muster. “Okay, son. I’ll be right there.”

I ran back to my original spot and waited a few more seconds. “C’mon Dad, where are you?”

Back to my deep voice. “I’m fishing. I’ll be right there.”

“Mom says to hurry up before the food gets cold.”

“I’m almost done, son. I’ll be right there.” I made sure to throw in the word, son, because I figured that’s how dads talked. When I was younger and my dad visited, he always called me, son.

I waited a couple more minutes and then made my way out of the trees and back toward the campsite.

“Mom, dad says he’s fishing and he’ll be right there.”

Mom was alone by the time I made it back to her. She had a funny look in her eye. I like to believe I earned an Academy Award that day.

#####

Mom’s original name was Francis Pepper Elliot, born May 1, 1927. Her father was a San Francisco bootlegger named Clarence Elliot. According to Mom, Clarence named her Francis because an Indian friend named Doc Francis brought her into this world and Clarence wanted a boy. According to my grandma and Grandma’s sister, Aunt Billy, mom was a handful to raise. Mom told me they sent her to a convent, but she ran away and got pregnant with my sister. My sister’s father was a man named Curl. Mom said he joined a traveling rodeo shortly after my sister was born and died in an accident.

What I know first-hand is, sometime between that summer in New Mexico in 1966 and the day in 1978 when she bluffed her way into the Mai Tai restaurant, alcohol staked a claim to her soul.

#####

It was spring or summer, 1972. I was fourteen, Grandma lived with us in Minnetonka, Minnesota, and my adult sister and her family were visiting. We’d come a long way since New Mexico, and by now, dinner in Mom’s house was always a formal affair. It was important that all the silverware be in the proper places, with a lit candle in the middle. Mom asked me to set the dinner table, but Sean, my three-year-old niece, wanted to do it. I let her.

Mom walked in from the kitchen. “Who set this table?”

That was when I noticed much of the silverware was missing. And maybe a few plates. The candle might not have been lit. “Sean and I did, why?” I figured everyone would think it was cute. I figured wrong.

Mom’s face contorted. “What the hell is wrong with you that you can’t even set a table? How many times do I need to tell you how to set a g**-d**** table? What the hell is wrong with you? And I told you to set the table, not Sean. Why are you so lazy?”

“Mom, it’s just silverware. What’s the big deal? I’ll fix it.”

She stomped her feet, pounded the wall, and wailed as if somebody were ripping her guts out. And then she went to the ground, kicking and screaming, and pounded the floor with her feet and fists. It was a toddler temper tantrum, but it was my own mother.

Mom climbed back to her feet and Grandma took her elbow and directed her toward the kitchen. “It’s not anything big, Francis. Just let it go.”

Mom shook loose. “I know setting the table is a little thing. But all those little things he does add up and now it’s a big thing. And he never stops. He just keeps pushing and pushing and pushing and he’s driving me insane.”

“I know. He makes mistakes. But this one is just a little thing. I’m sure he’s sorry.”

“No, he’s not. Just look at him, sitting there like a lazy, spoiled brat. I can’t take it anymore! He’s pushing me right over the edge and he doesn’t even care.”

My guts churned. No way was I that bad. And grownups were not supposed to act this way. “Mom, you’re acting like a baby.” Sensitivity was never my strong suite.

She stomped down the hall into her bedroom, wailing, and slammed the door. The walls shook.

Everybody sat for a few seconds. Until my unofficial stepdad, Joe, looked toward the bedroom and said, “Well, if you’re not eating, I’m not eating either.” He stood and walked down the hall into the bedroom.

I stormed out the front door. My sister followed.

She begged me to come live with her family in North Carolina. She told me nobody should put up with this crap and we could leave right now if I wanted. I knew she was right. Mom was sick. My whole family was sick. And I was in the middle of it.

I never told her how much she tempted me that day. Or how much her words meant to me over the next several years. But I turned her down. I had already tried to leave once back in eighth grade during another drunken episode. That worked out badly. And, so I made a decision to stick it out until I could leave on my own. I would find a way to survive. I went back inside, sat at the table, and helped myself to plenty of food.

Mom came out of her bedroom later and yelled at me for ruining the food she’d worked so hard to prepare. And now she had to throw it all away. I told her if she didn’t want it, I’d put it in the refrigerator and finish it tomorrow. I was hungry and needed to eat; she could starve herself if she wanted.

#####

There had been plenty of drunken incidents before that night, but this one was a turning point. Mom’s temper tantrums were her own fault, not mine. My sister confirmed it. But if I wanted to stay until I could leave on my own, I needed to learn to adjust. Because plenty more drunken temper tantrums would follow.

One time, Mom got mad decorating the Christmas tree and threw it outside into the snow. Another time, Joe had out of town business guests in for dinner, got drunk, and decided to entertain everyone in his underwear. Mom, also drunk, nearly bit his head off. Dinner table temper tantrums became common, with Joe following her into the bedroom nearly every time. And with every dinner table tantrum, I was left alone with all that food for myself. I always ate well and usually put the leftovers in the refrigerator before Mom came out to throw it all away.

A couple times, I pushed Mon’s buttons on purpose. But mostly, I learned to stay away from them, except at dinner, when I had to sit at that table with all the silverware in all the proper spots and a lit candle in the middle.

#####

Mom married Joe Gent on Friday, June 13, 1969 at the Camelback Inn in Phoenix, Arizona. Joe said he had been sober for three years. He gave me a copy of the Alcoholics Anonymous book, and I read it cover to cover. It was filled with stories about Americans in the 1930s who lost everything to feed their alcohol addiction, but followed the twelve steps and recovered. The book said if an alcoholic takes up drinking again, sooner or later, they’ll end up in worse trouble without help. And on Mom and Joe’s wedding night, they stood in front of all their guests and drank happy toasts. I had a bad feeling that night. And over the next years, home life with Mom and Joe descended into hell.

Nobody harmed me physically, and through high school, mom got up every morning and cooked me breakfast. But every night, she got drunk and reminded me how much she sacrificed for me. Next morning, she got up early again and fixed breakfast as if nothing happened the night before. She did it day after day, year after year, until I left for college.

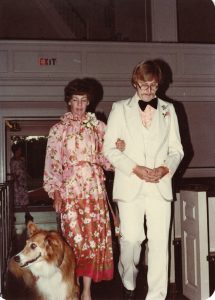

When Tina and I got married in August, 1978, Mom and Joe made drunken fools of themselves in front of my friends and half the town of Crawfordsville, Indiana. During our wedding and at the reception later, mom sat in a chair and glared at everyone—and talked to no one. When I graduated from college in 1979, mom showed up, threw a watch at me, and stomped away. When Joe died in 1983—alcohol indirectly killed him after they both went through alcoholic treatment that didn’t work—Tina and I drove from Chicago to Williston, North Dakota to help her settle things. She was drunk when we showed up.

I told Mom she could live with us if she wanted, but she would be living in my house with my rules and no alcohol. Instead, she found an apartment in Boise, near my sister. I visited a few times, and every time she looked worse than the last time.

#####

The AA book didn’t tell me how children of alcoholics learn to cope with the insanity around them. I figured that out that on my own. I was thirty-eight years old when I learned the words, don’t talk, don’t trust, don’t feel. Looking back, that’s what I did. Yes, it sucked. And yes, it colored my adulthood.

While living in my own private hell as a teenager and watching Mom slowly kill herself, I promised myself I would never fall prey to substance abuse. I kept my promise. But it was the wrong promise. Since I never developed a substance abuse problem, I figured that made me better than her. But I developed plenty of other problems, and I nearly destroyed my own family in 1995.

#####

I was mad at Mom almost until the day she died. Who wouldn’t be? But I’m older now, and I’m a Christian, and God commands me to forgive everyone who wronged me. That’s why God sent his son to die on the cross. But I’m not God, I’m Greg, and it’s not easy.

My sister took care of Mom for the rest of her life after Joe died. In 2007, my sister needed to put Mom in a hospice. I visited in April. This fearsome force of nature who could fool drunken Indians, bluff her way past a maître d, and slice me apart with her tongue, lay in bed in front of me, fully clothed, but also naked. Her red hair was silver-grey. Much of her mind was gone, but her eyes pleaded for mercy.

She asked me to read her a story and the only thing I could come up with was Ecclesiastes. King Solomon wrote Ecclesiastes in his old age. This is how it starts:

The words of the Teacher,[a] son of David, king in Jerusalem:

2 “Meaningless! Meaningless!”

says the Teacher.

“Utterly meaningless!

Everything is meaningless.”

Chapter two starts like this.

4 I undertook great projects: I built houses for myself and planted vineyards. 5 I made gardens and parks and planted all kinds of fruit trees in them. 6 I made reservoirs to water groves of flourishing trees. 7 I bought male and female slaves and had other slaves who were born in my house. I also owned more herds and flocks than anyone in Jerusalem before me. 8 I amassed silver and gold for myself, and the treasure of kings and provinces. I acquired male and female singers, and a harem[a]as well—the delights of a man’s heart. 9 I became greater by far than anyone in Jerusalem before me. In all this my wisdom stayed with me.

10 I denied myself nothing my eyes desired;

I refused my heart no pleasure.

My heart took delight in all my labor,

and this was the reward for all my toil.

11 Yet when I surveyed all that my hands had done

and what I had toiled to achieve,

everything was meaningless, a chasing after the wind;

nothing was gained under the sun.

My sister stopped me right here.

Mom looked ready to cry. I wanted to tell her I forgave her. But I could not just say, “I forgive you” when we both knew all the history. That’s probably why Ecclesiastes popped in my head. King Solomon was trying to tell us everything we do in this life is meaningless. Suffering or riches, easy or hard life, accomplishments or failures, none of it matters. All that matters is obeying God, and I wanted Mom to know we could meet in Heaven where everything would be good. She put me through hell as a teenager, but now I was a grown man. I could forgive her because eternity is a long time and I had already spent too much of it being mad.

But I never got a chance to say any of that because my sister stopped me from reading Ecclesiastes and gave me an ear full of grief for bringing all this up with Mom on her deathbed. Which was okay, because I probably would not have said what I wanted to say very well. And I have a hunch those first few verses in Ecclesiastes said everything that needed to be said anyway.

Mom understood. Call it a connection between Mom and her son.

She died a few days later, about two weeks short of her eightieth birthday.

As I write this in late 2018, for the first time since my preteen years, I miss her. I have so many questions about how she raised my sister and me. And about a middle child she gave up for adoption. And questions about a million other family legends. Back in 1998, something told me to call Mom and tell her about Jesus. I did, and when I asked if she would accept Him, she said yes. And, so maybe when we meet in Heaven we’ll finally hash it all out.

Update, September 2022

It seems Mom carried even more secrets to her grave. Charlene “Charle” Walker contacted me on Tuesday, September 6, 2022. She’s the middle child I mentioned between my oldest sister, Toni and me, born 1954. Today, Charle lives in Oklahoma.

Apparently, Mom met a couple in a chiropractor’s office, and they adopted Charle. Charle’s father was Robert Herbaugh. He was an alcoholic and an abuser. Mom left him and Married Doug Bean, and they created me in 1957.

My sister, Toni, has no memory of any of this. But she was only nine years old in 1954.

Charle’s son, Chris, has great taste in books. Charle told me that Chris bought a copy of Bullseye Breach and Virus Bomb.

Charle called Doug in the 1970s, looking for me, and Doug said I wasn’t there. But Doug had no way to know that Daniel Gregory Scott replaced Daniel Gregory Bean sometime in the summer of 1966 when Mom took Robert Scott’s last name. During that summer, Doug tracked Mom and me down at the Holiday Inn in Albuquerque during one of our stays. He called, and Mom told Doug we were headed to Florida. But we never went to Florida and I started fourth grade in Albuquerque. By the time Charle called in the 1970s, from Doug’s point of view, I had disappeared from the universe.

Mom went to alcoholic treatment in 1981 at the Heartview Treatment Center in Mandan, North Dakota. When Tina and I visited for family week, patients in her support group told us that a middle child had contacted Mom, and Mom was upset. Doug told me about his contact in one of our visits in the 1990s. That’s how I knew about the middle child between Toni and me.

Mom’s name at birth was Leila Francis Elliot. No doubt, her first name came from her aunt, my grandma Rose’s sister, Leila Bell Songstead, or Aunt Billy. That might explain why Aunt Billy seemed to take a special interest in me, even flying from Phoenix to Indiana for my wedding.

Mom was born in Flagstaff, Arizona, not San Francisco. Clarence Elliot never existed. His name was Clarence Minnerly, and he was Grandma Rose’s second husband. Grandma’s first husband, George Devil Elliot, was my grandfather. As far as I know, I never met him.

There’s more.

In 2018, Charle signed up with ancestry.com and learned that Robert Herbaugh fathered another daughter with Mom named Kathy, and a son named Richard. Richard died as an infant. A family adopted Kathy, and her name today is Kathy Kensmoe. She lives in Kansas City.

Toni’s father, Mr. Curl, also fathered another child with Mom. His name is

I am grateful to Charle for spending fifty years finding all of us, and for uncovering some of Mom’s secrets.

Recent Comments