We never know what influence we might have on other people. One sentence might change a life. That’s what Mrs. Will did for me. She was my fourth grade teacher for a few short weeks at an elementary school in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

It was late summer, 1966, and Mom and I were stranded at a Holiday Inn in Albuquerque after GMAC repossessed her car. Mom always said we were bohemians, but with no car and no money, we were about to become bohemians on the street. Somehow, Mom found a job and a place to live, and the nice lady who worked behind the counter in the hotel restaurant drove us to our new home.

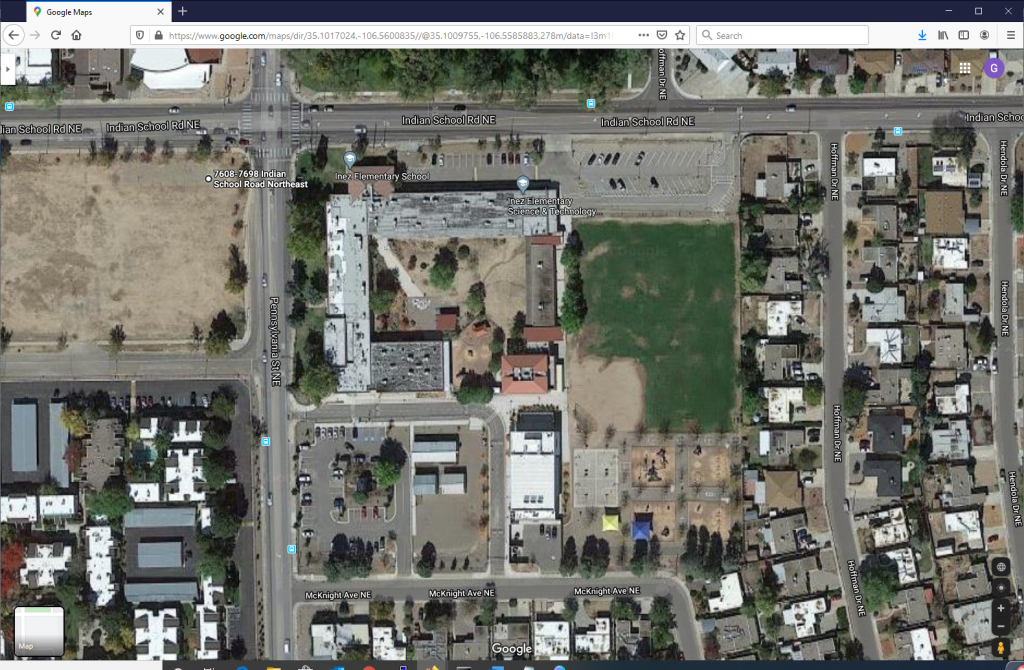

We settled in and Mom enrolled me in the elementary school on the other side of a chain link fence separating our bedroom-sized gravel back “yard” from the school grass field. I had been in six schools since kindergarten. This would be number seven.

Mrs. Will was my teacher. She was tall with poofy black hair. I liked her, but something was different about how she carried herself and I couldn’t figure out what it was. Maybe she was a Communist. Mom said Communists were different than us and wanted to kill us. I wasn’t sure I wanted a Communist for a teacher, but as the weeks went by, she never talked about Russia or China taking over our country, and so I decided maybe she was okay.

Mom had told me not to talk about our business with anyone; people can’t be trusted and besides, our business was none of their business. But somehow, Mrs. Will knew things about me I hadn’t figured out yet.

It wasn’t like she knew my detailed history, although there was plenty of material to draw from. Mom and I had been to Mexico, Canada, and nearly every western state. I had seen my grandpa hollering out a hospital window in Colorado Springs, walked all the way home from kindergarten one day in Twin Falls, Idaho, got off the school bus at the wrong stop in first grade in Tucson, Arizona, stayed with my grandma for a few days in second grade while Mom married Pappi Martin in Las Vegas, only to find out he was already married to somebody else, ridden in the car from Tucson to Canada with Mom and her artist friend, Robert Scott, instead of finishing third grade, taken his last name, and outsmarted a drunken Indian near Taos, New Mexico after Mom left Canada and drove to New Mexico that summer. Mrs. Will might not have known all that, but she knew something was different about me, and the more time I spent in her class, the more I realized she was right.

I met Karen in Mrs. Will’s class. She had short blond hair and I was nuts about her. Somebody’s Dad had a truck and one night, lying on my back in that truck bed, I looked up at the New Mexico stars, and all was right with the world because Karen would sooner or later be my girlfriend. That feeling quickly gave way to a yearning deep in my gut for Karen to be lying in that truck bed right next to me.

One day, all the fourth grade classes sat together and Mrs. Will and the other teachers showed a movie. Karen and I sat in back and held hands in the dark. My whole world shrank to Karen, and I wanted that movie to play forever so I would never have to let go of her hand. I decided right then and there, I liked Albuquerque just fine and did not want to move anywhere, ever again.

The school main entrance faced away from where we lived, and so the normal walk home meant I had to start the opposite way, turn right and walk to the street, turn right again onto the street and follow it past the school, and then turn right onto the street leading home. There had to be an easier way.

I found the answer a few days later. The school building had a back door. Walk out the back door, cross the field, climb the fence, and I was home. The challenge was climbing that fence. It was a little bit taller than me and the tops looked like rows of “X” shapes. Instead of folding down, the sharp chain link ends poked up at a 45 degree angle, ready to impale anyone foolish enough to try to climb over them.

At first, I walked home alone. But it didn’t take long for a few other boys to follow me. A few more eventually followed, and a few more after that, and before long, I was the after-school ringleader. A few girls even followed, but not Karen, and none of them ever tried climbing that fence. It was funny; I was the new kid in school and I showed these kids the shortcut they never knew about. I fit in just fine.

We had daily discussions about the best technique to scale that fence and we all understood a slip would be devastating to our futures. We got pretty good at it.

Until my foot slipped and something tore through my shirt and left breast. Mom was going to be mad when I showed up at home with a hole in my shirt and I would have to explain how I tore it. I looked down and found a pure white, roughly circular shape where my left breast used to be. Wow, this must be what the underneath layer of skin looks like before the sun tans it. And then blood poured in and all around that white circle and down the inside of my shirt. Somebody ran and got Mom, and somebody brought Mom and me to the hospital Emergency Room. The doctor put ten stitches in my breast and told Mom, if I was a girl, I would never forgive him. I wore those stitches and the scar they left like a badge of honor. Karen was not impressed, and Mom threatened me with my life if I ever climbed that fence again.

One time, Mrs. Will’s face clouded and she told me, no matter what happens, no matter where we move next, always learn to adapt. “You’re good at that,” she said. “I’ve seen you adapt here and you’ll adapt everywhere you go.”

“Why do you think we’re going somewhere else?”

“I just know you are.”

“But how do you know?”

“I just do.”

She was smart like that.

A little while later, she assigned a class project. Make a three dimensional map of North America using cardboard, flour, water, salt, and paint. I poured myself into the project. Mom even helped. She said she was born in California, and she had been to even more places than me. We both thought it was neat to make a map that had all the places we’d been.

I had to turn my map in early because Mrs. Will was right. Mom said we were heading to Phoenix to stay with Grandma’s sister, Aunt Billy for a while. It would be another new living situation and another new school in another new city. And we were traveling there on a real airplane.

Mrs. Will left me with these words. “Remember what I told you. Wherever you end up, learn to adapt. I know you will. Just like you did here.”

I never saw Mrs. Will or Karen again.

There would be three more schools in fourth grade, and twelve schools by the time I graduated from high school. Change would be the only constant in my young life and my teenage years would be hell on earth with alcoholic parents. But I remembered the lesson Mrs. Will wired into my brain. Learn to adapt. One teacher who cared made all the difference in the world.

Thanks, Mrs. Will. I owe you one.

Thanks for sharing the story, Greg. I’ve known you for a few years, but had not known how very peripatetic your formative years were. Please continue mining that wealth of experiences.

This morning on YNB, you posted a link to this blog. I’m happy you did. This story pulled me in because I, too, moved around through elementary school. There’s something more. You write as if talking to a stranger who is a friend. I even got attached to Mrs. Will and Karen. I’ll read more of memoir since that’s my genre.

Thanks Candy! I wish there was a way to click “Like” on your comment. You made me all emotional. Now I gotta go find a movie where stuff blows up. 🙂